WE DON'T BUILD SPACESHIPS. WE ARE SPACESHIPS.

Interview

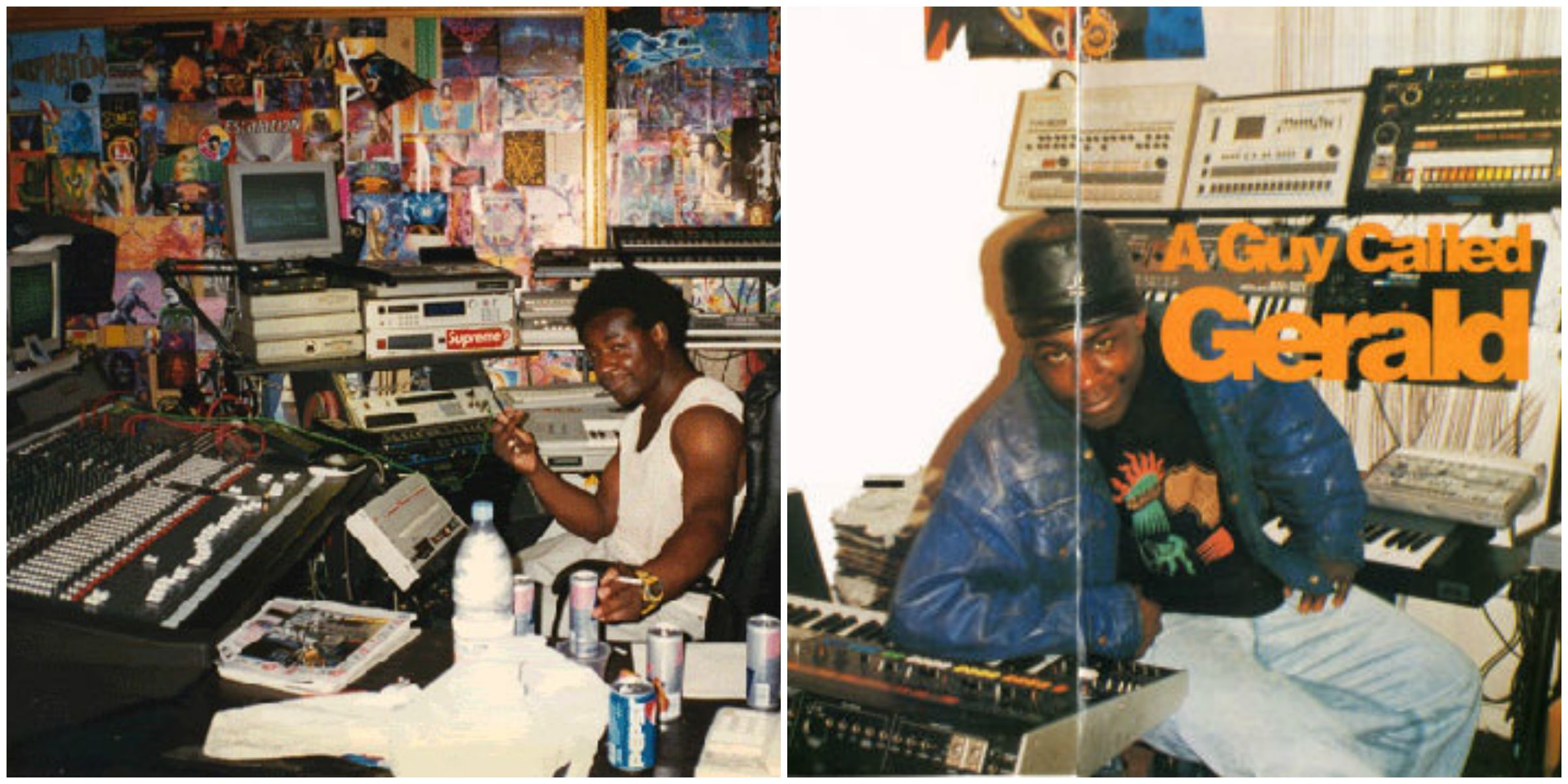

Breakin’ Beats: In Conversation with A Guy Called Gerald

“If you don’t know where it’s from, you will never know where it’s at.”

Gerald Simpson’s art and contribution to the world of music categorically precedes what’s now known to new-agers as the “global dance music industry”. Back when Simpson was getting his feet into club doors to spend hours cutting shapes to electro-funk and jazz-funk, the music scene had no real corporate allegiance, big-name branding or wanton brown-nosing (which, in a way, is also its own industry). The Manchester of the ’80s is a far cry from the Manchester of today, and possibly even further away from most global clubbing cities, of which Bombay, where Simpson happens to be playing his next show and first in India, is clearly not one (yet).

In the musical clime of 25 years ago, it didn’t pay to to follow the herd (not that it does now), and being unwilling to innovate and revolutionise would, to a sane person, be considered career suicide. So, when he made the switch from the Gerald Simpson of 808 State fame to his markedly more infamous, new personality which would later be dubbed ‘A Guy Called Gerald’, it could well have been a careful, deliberate departure, a proverbial (but not permanent) sayonara to the acid analog groove music 808 State had helped publicise beginning 1988. Instead, A Guy Called Gerald took the hard road, and ultimately, the more fulfilling one.

The last decade has seen the word “pioneer” thrown around so much that it’s meaning has surely mutated. Today’s producers are not the Richard D. James’, Jeff Mills’ and Gerald Simpsons who were driven to innovate almost always. Today’s producers indubitably have the benefit of what’s known as an established market and an easier gateway to fame (if that’s solely what they’re after). This is primarily because of the way music is peddled and consumed in the age of the Internet. In that sense, A Guy Called Gerald pre-dates this new economy of music because his creations and expressions revolve around the very heart of music – a steadfast allegiance to melody, rhythm and the dance floor groove, more spiritual than merely physical and material.

[For a crash course on ‘groove’, check out this Berklee School of Music blog explanation , and this Resident Advisor feature. For the serious reader, here’s a link to an in-depth academic journal titled ‘Syncopation, Body-Movement and Pleasure in Groove Music’ that offers myriad explanations and scientific connections.]

If none of that is your cup of tea, take Dee Lite’s words as gospel, scan through Simpson’s own manifesto and read on, because today, we speak at-length with the breakdancer, producer, sound designer and tastemaker known as A Guy Called Gerald. We talk what dancing in clubs looks like today, get him to namedrop some dope disc-jockeys from the hey days plus some great early records, followed by a note on his hardware, the need for a history lesson in music for today’s audiences, solid tips for future producers, and his impending foray into sound re-production in clubs.

भ | Hi Gerald! If I’m not too far off, your musical education began in the ‘80s with soul, funk and jazz. Did those primarily-American styles of music have many takes in England when you had started to tune in?

They probably had more than you would ever know. In the community where I grew up, that is all we had. We couldn’t go down the pub and talk about football as we were not welcome. The soul, funk and jazz actually came later – my musical education started with blue-beat and reggae.

भ | Can you tell us a little about Manchester breakdance scene and your first times at The Hacienda?

Manchester breakdance scene started a few years before the Hacienda in the early ’80s. For me it started around the time when the movie Wildstyle came out. We would suck up any documentary or anything that we saw on the scene. You have to remember there was no internet so we had to make up a lot of the stuff ourselves. We used a lot of imagination.

भ | Who were the top tastemaker DJs that were really making dancers work?

Pre-breakdance era there was loads of DJs – one of the ones that stood out for me was Ewan Clarke who used to play at a lot of the youth clubs. It was very underground and he’d play, what was at the time, very obscure jazz fusion – Chick Corea / Dave Valentine / Airto Moreira and then he would mix it up with some funk – Slave. Before breakdancing there was a big dance scene in the black clubs. Other DJs we had Greg Wilson, Mike Shaft, Colin Curtis, Stu Allen, Kev Edwards, Chad Jackson. There were many more but I could probably name more dancers in those days than DJs.

Stream No Sell Out – Electro Retrospective by Greg Wilson (via Electrofunkroots)

भ | Do you still cut shapes when you’re out on the town or while you’re home jamming out some tunes?

Yes I think it’s important to keep dancing and also it feels strange not to. I noticed if I’m out – the feeling to want to dance is not so strong due to a monotone feeling where there is just not enough rhythm or groove. It seems a lot of what’s happening in production is just regurgitated loops. If I was going to equate it to a picture or a piece of art it would be just taking the nose of the Mona Lisa and printing it across the page 20 million times until it became a blur of nothing and then sell it to people as the same thing.

भ | What’s your take on dancing in clubs today? What we see here in India is a whole lot of those lazy DJ-booth-worship-moves, barely any interaction between pairs or groups of dancers, and the ubiquitous hand-in-the-air thing. Does that bug you at all? What do you think went wrong?

I think the regurgitation of other people’s moves or repeating things that they see. There’s no natural or true expression. I don’t think there’s any kind of inspiration coming from the music. To me it seems like the music does not allow for any kind of self expression. It feels like it’s a totally different culture to what I know. The sounds are very staccato. Every sound and every expression is on a grid. The kind of people involved from the production to the dancefloor would be better off line dancing. They feel safer if there’s a guideline so they need a handclap to fall in the same place every time, for the high hats to be a constant theme, the break down to happen at the exact moment in every single track and similar sounds to be coming in and out at the exact times – nearly every track.

Now if you think back to someone who only needs a groove – it is totally different. What’s happened here is the producer is sounding like the machine instead of the machine being used by the producer to enhance the groove which should be something that comes from their head. The producer usually has no background or memory of natural dance expression. So, therefore, the dancers who are there to be inspired, to express themselves and move in their own individual ways, don’t. Just machine motion.

Here’s a clip from Manchester in the year 1986 that shows black audiences dancing to house music (emphasis on dancing) with DJ Mike Shaft on deck duty.

भ | What jazz and electro-funk records were you into back in those days?

It’s a real mixture of stuff – from Big Daddy Kane, The Last Poets, Afrika Bambaataa, Miles Davis, The Eighties Ladies, Grandmaster Flash, Jazzy Jay, Shalamar, Slave, Slick Rick, Mantronix, UTFO… could go on forever.

भ | Recently, Derrick Carter spoke about cultural misappropriation in music in the hopes of starting a bigger dialogue that unfortunately lost its legs soon enough. Now, dance music culture in the UK, especially from a black perspective, has never been documented the way it should and could have been (the book by Snowboy being somewhat of an exception to this). Things began to get better with the beginnings of hip-hop, but the electro-funk and jazz funk movements in the UK haven’t been written about much at all. Do you think it important for younger generations of music lovers to have some sort of a written/oral/pictorial history in order to reach back and learn about dance music’s origins? And why?

I think it would be of value. Otherwise there is no root to what they have and without the root it will just fade back into rock ’n’ roll. Most people actually don’t realize where it came from and for sure it will definitely be forgotten without documentation.

There’s a few people like Greg Wilson who were there and do write about those times and the music so people can check his blog if they want to learn more.

भ | Other than a more well-rounded appreciation for the music’s original tenets, what do you think the Internet generation of house music fans stand to gain from these “history lessons”?

On my original Juice Box label (I say) “If you don’t know where it’s from, you will never know where it’s at” and I still believe that today. I hear so many people regurgitating stuff that they’ve read in a magazine that’s been repeated from other people repeating wrong information and it’s become cyclical. Their influences usually only go back as far as the early ’90s although often they’ll claim to have DJing when they were 4 or something.

I wish I had something like the internet when I was running around trying to find jazz records in the 80’s. I had to rely on the information on the back of the sleeve to find the tunes that I wanted. Miles Davis records were like the oracle for me because everyone played with Miles Davis. Whereas now all you have to do is put the name in youtube.com and then everyone that was related to their sphere comes up at the same time so there is no excuse not to go digging for information.

भ | Your penchant for performing your music live with hardware has a been well-documented. What were the first pieces of hardware you cut your teeth on?

Well, first machine was a drum machine in about 1985. I think it was a simple BOSS drum machine which had a step sequencer. It gave me the concept of how to program a drum machine. And then I would go to a music shop down the road from my house called A1 where I saw a second hand Roland TR808 and realized the sound was the same sound that was on most of the funk and electro funk records that I heard at the time. So I did anything and everything to get the money to put a deposit down on it and in the end I bought it for £150. And another shop down the road called Johnny Roadhouse I found a machine that had the same logo so I assumed that it would work together – it was a Roland TB303 which was being sold as a ‘band in a box’ with a Roland 606. No one wanted the machines in those days so they were very cheap. I then got hold of a SH101 and then from there I spent a lot of time locked away working out how to use them in my own way.

भ | And how did you go from that to, say, something like ‘Voodoo Ray’?

Well, it wasn’t until ‘87 that I had enough confidence to send demos to Piccadilly Radio. By then I had my own bedroom studio and was recording 90 minute tapes – probably one a week, so the equivalent of doing an album a week. Everything from proto acid sounds to experimental ambient fields. Only the 303 and 808 had sequencer memory so everything had to be instantly recorded onto tape. I used guitar pedals to create the effects.

भ | What advice do you have for people just beginning their foray into dance music production, especially those left confused by the abundance of hardware and software available these days?

First I would say follow your heart, know yourself then, meaning: don’t repeat every little thing that someone else has done because we have enough of that. I wouldn’t think of being a multi-millionaire from the music. Try and find your own style – in fact, one of the things is to learn the difference between style and fashion. It is not the same thing. There’s loads of different information about each bit of software and hardware that’s available. You have to take the time. The mountain stream will find the ocean. It doesn’t matter what you use. The machines are there to aid you. They are like your paint brushes – most of them do exactly the same thing – especially nowadays. You just have to find the right tools for what you want. No one can tell exactly what to get.

One legend takes on another here. Listen to Aphex Twin’s deep and funky remix of A Guy Called Gerald’s ‘Rhythm Of Life’.

भ | You’ve always been a supporter of technological innovation in music. Today we’re seeing hardware of all shapes and sizes, software doing things we could have never imagined. What do you envision as the next big step forward in music technology?

As far as I am concerned I think we have all we need for now. The producers need to learn how to use the machines and software to their full capacity before we start looking for the edge. The programmers who make the software are at the cutting edge but a lot of the people who are producing the music are still stuck in a loop in DJ world.

भ | What’s coming up for AGCG in 2015?

I’m working more and more on live shows. I’m working on a new way to present the music live based around the idea of being in the centre of the dancefloor and at eye level. The music sounds like it’s being played in a toilet. We are well into the 21st century now. Basically as soon as you monetize something then a formula is built because they have more to lose. So there are very few clubs that make sound the absolute priority. I am looking to create a space which mimics the studio environment – not only that – because I would be in the centre of the dancefloor so I can monitor everything around me and be at the same level – eye-level with the presumed dancer. This way it makes it easy for me to create the atmosphere and the rhythm suitable for the individual dancefloor. Kind of like an open kitchen in a restaurant – it’s an open kitchen in a club bringing the food to the people instantly – as soon as it’s produced it’s already on the dancefloor. What I’m looking for in 2015 is sound reproduction in the clubs being taken a lot more seriously than in the past.

भ | You’re going to be in India soon. Weren’t you supposed to be here same time last year as well? What are you looking forward to the most from this trip?

I was planning on a personal trip last year but had to cancel. I’m looking forward to the new experience.

भ | This is a personal question. Are you a fan of Level 42 at all?

Yes they were pretty interesting. They weren’t as left field as I got in jazz funk but they were interesting.

Listen to our picks of A Guy Called Gerald’s mixes below. First up, a DJ mix from the FACT Mix Archive, followed by a Live set at Labryinth in Japan in 2010.

A Guy Called Gerald plays a DJ set in Mumbai on Saturday, February 21st, 2015 at By The Pier. Tickets and event information here. Follow A Guy Called Gerald on Facebook, Soundcloud, and over at his official website.

Words by Abhimanyu Meer.